Expansionist Desires Continued….“Of course we can make that happen,” I responded in a haste gasp, barely catching my breath or noticing if I had interrupted him. “That’s precisely what we are here to do, Mr. Jacobs [the Soweto District Director from the Gauteng Department of Education]. We are hoping that the Lilydale deployment goes so well that we’ll be able to expand this program to schools, ideally, all over the country.”

“Good,” he said, as if I delivered the desirable answer he was anticipating. “I want to bring the XO to Soweto; have the entire district full of them. I want to move on this fast.”

I couldn’t believe my ears; was it really this easy?

“Then lets move,” I said without skipping a beat. “I will email you and your team,” who had, by this point, noticed an important meeting—their input could cost them a raise, a lack of it their jobs—occurring on the podium and, after meeting my gaze, made certain to pull up a few chairs next to the Director and I while Phindile assisted Nastya and John with the remainder of the grade 5 enrollment list, “tonight and get in contact with my OLPC Corps manager to discuss specifics such as costs. But tell me, how many XOs, or schools, are we talking here?”

The diversion of his eyes from mine and into an empty stare directed at the ground coupled with his delayed conversation indicated he had begun counting numbers in his head. The sun bounced on and off his thin glasses as I waited, momentarily taking a minute to glance at the jubilant cheers of learners rejoicing once a classmate was handed their very own boxed XO, the sharp edges of the cardboard box reminiscent of bountiful Christmas presents these children have likely never gotten.

“Roughly 13,000,” he said nonchalantly. “All the primary schools in Soweto.”

“What happened in Rwanda,” I said, wasting no time, “is that the Ministry of Education held multiple structured training seminars with all the teachers who would be involved in the multiples of schools at the forefront of deployments across the country. They also trained technical staff to ensure they could work more efficiently and independently of outside parties to strengthen sustainability. In addition, certain subject-specific modules were created to integrate the XO into the classroom.”

I was breathless. The sun bounced from head to head on the front podium row, off the District Director’s glass lens, and into my eye. I had positively overwhelmed him. One of his co-workers, an ever-smiling, nurturing woman named Lizzie, took the lull in voices to pick up where I left off.

She leaned forward, masking the pitch of her voice to ensure she wasn’t in competition with John and Nastya, who by then had barely reached labeling and distributing computer #20. “I think,” she almost whispered, “that we should invite them to the Gauteng Department of Education meeting in a few days so they can impress this idea on all the District Directors in the municipality.”

Irritated, Mr. Jacobs shot Lizzie a stiff glance and very slowly said, “That’s exactly what I don’t want.”

Lizzie and I, both finding ourselves in a forward-leaning position, automatically retracted our bodies at the sound of Mr. Jacobs’ surprising proclamation.

He continued. “I want Soweto to have this project first, and then when the rest of the District sees the laptop here, they will want to follow suit.”

With the exchange of a knowing look between us as brief as a bolt of lightning, Lizzie and I understood that the District Manager wanted the glory of an XO success story in his own Soweto jurisdiction—historically and presently one of the most disadvantaged areas in the Gauteng municipality—all three to set a precedent with the Municipality and the Federal government, ensure Soweto kids were reaping the benefits of a transformative, unique 21st century education, and take ownership of the project in Soweto in case the Gauteng Department of Education didn’t want to jump on board. Everyone has ulterior motives, I thought, but if his included offering youth who live in squatter camps, who are physically abused at home, and who will never imagine their lives to be silently interrupted by the four-letter killer in the next decade the tools to think differently about their circumstances and the potential to change them, then so be it.

“I understand,” I replied, faintly hearing Nastya and John begin calling out numbers in the 70’s. I quickly recalled Mr. Mohamed, upon introducing us to Mr. Jacobs, mentioning that the District Director, obviously a very busy man, could only make a brief appearance at the launch and that he would have other responsibilities to adhere to afterwards. I had to move. Directing my gaze at all three Lizzie, Mashooda—a young, tiny Indian woman who had also pulled up a chair next to the Director and I but had been relatively silent throughout the hasty discussion—and Mr. Jacobs, I concluded the conversation: “My group and I are absolutely thrilled that you are this invested in a much larger-scale XO deployment in Soweto and we’re very committed to working with you during the next few weeks so that this project can really see the light of day.” Now, setting my sights more at Mr. Jacobs’ administrative personnel who would try, as we earlier discussed, to raise money from corporate sponsors and contact the Gaunteng’s E-learning Director in hopes of garnering an ally in a key sector while Jacobs put his authoritative backing behind the project, I decided the XO could do the rest of the talking for me.

“I will put you in contact with our project director, Paul Commons, who will facilitate more serious discussions from a senior OLPC standpoint and maybe next week we could meet at the Department to discuss particulars. Would you mind typing your email addresses in this write file on the XO, please?”

They smiled and cautiously moved over to the little machine with a big mission and began, carefully pressing their fingers on the green rubber keys, to type their contact information. The students looked on in wild amusement.

Learner TrainingUpon completion of teacher training mid-July, as a group comprised of me, John, Anastasia, and Lilydale’s entire teaching staff—including the principal—we agreed that learner training would take place Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays after school for two hours. The 87 learners would be divided into groups of three and trained by John, Nastya and I in three classrooms next to one another. The training would occur for two weeks, after which we would use the same rooms, times, and days, to continue familiarizing the learners with the XO during an after school program that would be less structured in terms of learning the XO and instead focus on the students learning about themselves, using XO programs like write and record. This would indeed be the practical implementation of the student journalism proposal for which my team and I were awarded one out of thirty spots in the OLPC Africa Corps.

And so, precisely at 2:30 PM on Wednesday, July 22nd, approximately two hours after the end of the launch, learner training began. All XOs were numbered and charged and, after Phindile distributed laptops 1-89, children whose excited screams, shouts, and laughs infected the halls of the school more potently than a biological bomb, quickly filed into the classrooms, divided into three groups. Turned out I got the rowdiest bunch.

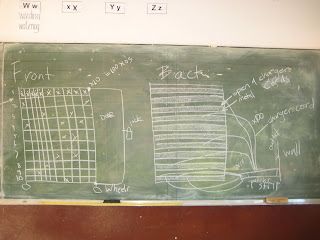

Each one of our training styles was unique to the person leading it. While John took a relaxed and reinforcing approach by allowing the learners the freedom to roam and experiment on the XO before instructing them and Nastya took a more structured method by using the chalkboard—which could barely contain the thousands of words pouring from it from the previous lesson—to demonstrate how to use programs such as write and scratch, I began my training the only way I knew how: with the basics.

Introducing the children again to me and my group and explaining the reason why we had so frankly impeded their usual schedule of euphoria and freedom at the sound of the last bell of the day, I told them that we were Americans working with the Kliptown Youth Program and Lilydale to help spread computer literacy and a more inclusive kind of education to the grade 5 classes at the school. The computer was made for kids, it’s got loads of both fun and educational programs installed on it with the capacity to install more with the help of the server, and it’s got mesh networks that allow you to chat with your friends, I said to a sea of wide-eyed 10-year-olds who intuitively somehow knew that chat was just another deviant of fun. I continued on with battery installation, powering the XO on and off, personalizing the laptop with the entry of your name, individual color, and talking about the programs, none of which the kids cared more about than the .ogg music files found hidden beneath obscure titles in the browse function and games such as maze and implode, although the ‘speak’ man’s digitized, monotonous, terminator-like voice came in as a close—and annoying—second in disrupting both my students and I during not only the first, second, and third, but fourth and last training sessions. In the two hours I had on that first training seminar, I set a solid foundation for the rest of the sessions, especially because I managed to begin actively explaining about the navigation of the laptop, including the ‘border’.

The second, third, and fourth seminars consisted much of the same plan in terms of laptop training, divided into a daily break-down of the day’s activities on the board, review from last class followed by questions, and usually two or three educational programs like scratch, write, record, wikipedia, moon, and read for the students to familiarize themselves with before I broke down and capitulated to relentless shouting—and polite requests coming from adoring eyes—to play “GAMES”!

However, the three sessions following the initial training did not go according to plan; practical issues such as the charging, transport, and storage of laptops—despite being discussed at length during teacher training—caused problems for reasons that could only unveil themselves during the application of such activities.

After training on the first day, laptops in all three classes had to be put away into the administrative building until a more permanent solution was found. But to relocate the laptops day after day following training seminars from classrooms adjacent to the administrative building would soon prove to both compromise the security of the laptops and make for very difficult and ineffectual XO inventory counts. About 20 minutes prior to the conclusion of the first training seminar, John, accompanied by a quiet knock, came into my room.

“We are going to finish up right away and begin putting the XOs back,” he said, watching my face for approval. My silence bade him to continue. “So I’m going to start calling numbers 1-10 right now and if you have any of those learners you can send them out to the courtyard,” he said, pointing to the open space behind him, “and I will put the laptops into boxes. We’ll do that in intervals of 10 until we reach 89.”

“Sounds good,” I said in a hurry, eager to get back my kids, who were, this excited and close to the end of the school day, beginning to summon chaos. “I’ll send out my 1-10’s right away.”

By simple virtue of the division of XOs into three groups, there was no semblance of order or sensibility in the devised system—that would become apparent in the minutes that followed.

My class contained no learners in the first batch, only a few in the second, many in the third, and a multitude of learners dispersed between intervals 40-89. Each time I called for the next group, the class would, already having lost focus of the XO because I taught them to shut it down in anticipation for its storage, begin to stand, move around, ask for permission to go the bathroom, and request to be let go, all things I had to avoid in order to make sure no XOs were stolen in the frenzy of the situation. In total, it took more than 45 minutes and many frazzled nerves to tally all the XOs and carry them back to the admin building to be charged, which was a problem in itself, as even with multiple power strips and several plugs, not all 89 XOs—11 were given to teachers—could be simultaneously plugged in at once.

The next day after school, with the grade 5’s swarming around their respective classrooms while the grade 6’s and 7’s gave us disdained looks, my group and I decided to take a more organized approach to the storing of laptops. This time, instead of being given learners whose numbers were all over the place, we decided to order the learners in ascending order, with me having the privilege of training learners who were assigned laptops 30-60. From now on, before beginning training, each member of my team would count the laptops entering their class, mark which learners were absent, distribute the laptops, and ensure the number of laptops left in the class after the departure of the learners corresponded to the initial figure. But since all the laptops couldn’t be charged the first day, the first hour of training on the second day was compromised and had to be utilized without laptops. I took this opportunity to get to know the kids who would soon bring tears of joy to my eyes in my most sincere and evocative African moment yet, and tell them about OLPC.

I told them about OLPC’s mission of granting a 21st century education to children who would never have had the opportunity otherwise. I told them that children who were maimed in Sierra Leone and the Congo due to extensive civil war were also using the XO at the same time to learn how to express themselves the same way we were going to do next week, a statement acting as a prelude to my next question.

“Do any of you know what journalism is,” I asked, pleasantly surprised at the speed arms began floating in the air. A pretty girl with braided hair raised her hand for the first but certainly not last time. I would soon find out her name was Phumelele, and she would become one of the smartest and most eager students I would have. With confidence and poise seldom found in a girl that age, she began to speak.

“Journalists,” she said, “write stories.”

Brief yet accurate to a tea, I concurred with her. “Yes,” I said, pleased at her courageous intellect, “and it’s never too early to start writing stories about yourselves.” Realizing I had the undivided attention of the class, I wasted no time. “Other than to teach you about the XO, we are here to help you learn about yourselves and each other. Next week we will begin that project using write, record, and maybe the internet if it is setup by then.” At the mere mention of that word, the class erupted into enthusiastic whispers, at which point I had to quell their hopes.

“But we don’t have internet yet, so let’s continue with the training. Who wants to help me carry the XOs into class?”

Running towards me with a look of perpetual Christmas in their eyes, I had now to choose three volunteers from dozens of buzzing kids.

Parent MeetingAfter approaching Mr. Mohamed with the idea of meeting with parents of the learners involved in the Lilydale OLPC project during one of our first conversations with him, Mr. Mohamed drafted a letter that requested the presence of all grade 5 parents at Lilydale on Saturday, August 1st, to inform them of the project and create an awareness around the XO that could potentially foster joint ownership in the future and mitigate security concerns.

As the first rain in months fell hard and fast from every corner of the dismal grey sky above us, that first day of August we drove into the Lilydale parking lot, taking curious notice of the very few cars and people surrounding us.

“Hurry up,” Mr. Mohamed’s accented voice sprang from inside the administrative building, his arm motioning us forward. “The meeting is across the yard.”

We were taken to a room full of approximately 15 people, mostly women—or mothers—of the total 89 learners in the grade five class. Whether or not the rest of the guardians decided to forfeit the meeting because their children did not deliver the alert, because it fell on an early 1st of the month, or because the weather was reminiscent to Noah’s Arc, it didn’t matter; here were 15 parents eager to learn about the ‘school in a box’.

After a lengthy introduction about OLPC, the XO—which was, at this point, being passed around from one astounded parent to the other—and the policies associated with the program, we were met with a cacophony of crickets after asking the parents if they had any questions or comments. After a few minutes pause, one lanky woman with a leather jacket and a white knit hat stood up.

“I want to thank-you, your NGO, and the man who used to go to this school and is now the Director of KYP for bringing these laptops for our children,” she said slowly, pausing after each passing word so as not to fumble her appreciation. “When my daughter came home every day last week, she just couldn’t stop talking about the laptop and said she even finished some of her homework for class using the computer. She is so happy and so are we.”

Murmurs of gratitude reverberated from the crowd to us and vice versa. But the lady in the leather jacket had a more important point to make.

“Is there any way that the children could take home the laptop? Or, if not, if they can be purchased individually?” Before we had a chance to dart our eyes—which harbored a look of inability to single-handedly answer the question—to Phindile and Mr. Mohamed, both of whom had expressed their disapproval at joint-ownership because of security and trust concerns, she concluded her statement and took back her seat. “We don’t have a lot of money, but we would do anything for our children’s happiness.”

We regretfully explained that although joint-ownership is an integral part of the OLPC program because it not only allows the learner to take incentive and excitement in their own learning, but multiplies the potential of the learner by allowing unhindered, private access to the tools on the XO, we were neither experts or locals in the community and had to heed the advice of our Lilydale partners, who could possibly still allow learner ownership once efforts at increased community awareness were in place and the learners showed a dedicated responsibility towards the XO.

As the meeting concluded and the parents signed their names next to their children’s on an attendance list at the front of the room, the XO’s record function capturing the movements of the crowd elicited ecstatic oooh’s and aaaah’s.

Power OutageOne sunny morning a few weeks ago, Brucie intercepted my daily breakfast of oatmeal, yoghurt, and tea to tell me a story—well, a couple stories. What started as a discussion about post-apartheid South Africa—business that lost human capital when, because of the active enforcement of affirmative action laws, (officially called Black Economic Empowerment) skilled whites were fired to make room for semi-skilled blacks—ended with an explanation about a national problem that, at least by the initial sounds of it, has little do with color: electricity. Ignoring warnings that came in the mid-80’s and perhaps even earlier about a looming electricity crisis, South Africa’s top industry leaders and politicians faced a rude awakening during the dawn of a new democratic era whose lack of planning threatened to eclipse the humanitarian gains of the post-apartheid era. To avoid serious electricity problems in the most affluent country on the continent would necessitate either the building of more water dams, wind turbines, or the extraction of more coal, all of which options were either unexhausted or untapped ten years ago. Today, regardless of what skin color one was born with or the relative prestige in which one lives, the whole of the South African population is reminded that electricity remains a scarce commodity, stretching from daily TV warnings similar to American ‘Amber Alerts’ or ‘Terrorist Threats’ to entire days without power—a reality we had to for several days confront last week at Lilydale when we were forced to forego XO-classroom integration on Monday and Tuesday.

Confinement[Editors Note: On a short break from reading Hunter S. Thompson’s ‘Kingdom of Fear,’ I’ve decided to take a more ‘gonzo’ approach to my writing; brisk, blunt, and fearless, I will emulate his indefinable style in an effort to find my own. ‘Long Walk To Freedom’ inspired me in much the same way and honed my use of descriptive metaphor.][Read at Own Risk.]It is neither pleasing nor easy being stuck in one of the most beautiful and historically rich countries on earth with no money, no plan, and all the time in the world; although it allows for more ample reading, writing, and introspective time, it downright sucks and after countless hours and endless days, provides for one of the most regrettable activities ever. Despite undignified, prolonged begging from the University of Massachusetts Boston, we were given no grants and no pity for this project. As a result of little additional funding on top of the $10,000--$8,500 of which was used on plane tickets—very generously provided by OLPC, my group and I have lived a limited reality for the last several weeks. On top of being activity-less—there is much time left over after leaving Lilydale, during the afternoons, and those popular three-day breaks I’ve come to loathe: weekends—the three of us are living in a small—yet comfortable and nothing to scoff at—flat with a shared bathroom and competing personalities. In an effort to escape perpetual confinement—of body, soul, and mind, you bet—and flirt with life just a little, I a few weeks ago decided to get a month-long membership at the plush, amenity-full gym across the street: the always bustling, ever-modern, never-dirty, Virgin Active.

It is in these two hours that I can listen to music, sweat intensely, and, in a carefully rehearsed speech, explain who I am, where Boston is, and what on earth I’m doing with a one-month ticket to fitness in the middle of South Africa’s most intimate ‘township’. My trainer, Lucas, a young Xhosa guy with rock-hard abs and a steely work ethic, often times acts as my new best friend; we’ve even started training together and doing the repulsed by some, envied by all, fist-punch.

“Sorry I’m late,” he says to me with his characteristically big brown eyes and uniform smile as he sits next to me on the stretching mat in workout gear. “How was your day?”

Although I’ll answer in short, Lucas—or any other human being who is not my parent, lover, best friend, or hairdresser—will never get the full story of what’s going on inside that thick head of mine or the consequent feelings inside the deepest bowels of my beating heart.

“Are you going to tell me what’s wrong,” he asks for the second day in a row, waiting patiently for an answer that may offer a morsel of truth, unlike yesterday’s “it’s no big deal” response.

Everybody knows that posing such a loaded question such as ‘How are you,’ or ‘How was your day,’ to a complete—well, almost complete; he has seen me sweat—stranger is only a polite formality that the questioner never really wants answered but rather expects a bland, monotonous reply to. But since he is a good, honest man (he’s only charging me half price, 50 Rand, per hour), I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt: Even if he was interested in my rambling about my metaphysical inability to transgress the physical barriers preventing me from roaming my mind and the vast valleys of the Transvaal (the former term for the municipality of Gauteng) that I’ve read about with salivating, vivid envy in ‘A Long Walk to Freedom’, it wouldn’t be right to unload on poor Lucas. Besides, I don’t feel like talking about it; being at the gym has pacified my nerves and (temporarily) palliated my confinement. Live in the moment, I tell myself.

“Nothing, Lucas, really,” I half-lie to him. He knows I’m holding something back but he doesn’t poach—I knew he didn’t want the burden. “So we doing 10 speed and 1.5 incline for another dreadfully revitalizing 12 minutes today, Lucas?”

His smile warms my senses and palpitates my heart. Time for the death run.

Two hours have passed and I am drenched in sweat. I bid Lucas goodbye and thank him sincerely for yet again kicking my ass. I feel good—but not as good as I’m about to feel when I step into a luxury known all over Canada but surprisingly less so in the bottomless pit of capitalism itself, America: the steam room. All the women in the steam room—large enough to fit close to twenty standing women, maybe 15 sitting skinnies—are naked. They were yesterday, the day before, and they continue to be today; and so, trying desperately to assimilate to the society I have become a part of, I decided the week before last that I would go naked too.

My parts bouncing up and down, I brazenly tiptoe into the scathing mist, only to be turned back—and on no nice terms.

“We shower before entering the steam,” says a lady who looks like the rest in the steam room, their features barely discernable in the fog that blocks my detailed dissection of my confronter. “See,” she says annoyed, pointing to a sign behind my back. I turn around to read the obvious.

ALL PATRONS MUST SHOWER BEFORE ENTERING THE STEAM ROOM.

Feeling defiant yet aware of fighting a losing battle, I concede to wash myself ‘before entering the steam room.’

Opening the door only slightly and closing it at cheetah-speed so as not to upset any more steam room wardens after my bitter shower, I am blinded by the white steam; all I see behind it is figure-eight silhouettes (be assured there is no shortage of curves in a South African steam room). After literally taking a stab in the dark and climbing over heads and stretching my legs in compromising positions (for the ladies underneath me) to reach the most sought-after spot in the steam room—the top corner, I plop down and am automatically enveloped, tickled, and warmly embraced steam and the calming sound of Zulu gossip. Confinement never felt so good.

Thieves in the NightBefore going on this trip, I spoke to many so-called African ‘experts’ who, despite having had very unique personal experiences in Africa and South Africa and offering me contrary pieces of advice, all warned me that no matter what I would or would not live through, what I would or would not have not seen, how long I had been in the country, or how comfortable I could have possibly felt, to never, ever, ever, they repeated, let my guard down.

Well, I did. I let it down when I felt that, after living amongst alcoholics, beggars, cheaters, abusers, addicts, thieves, children, teenagers, medicine women, Rastafarians, community workers, pioneers, and extraordinarily good people in a slum in one of the most crime-ridden countries on earth, I could survive not only anything, but everything and everyone, and forgot to put my iPod away. I let it down when I walked home alone from the field I used to run at in Kliptown. I let it down when, after being stranded at the gym one night, I allowed one of the managers to drive me home after dark. There must have been other times my common sense eluded me for instinctual spontaneity and chance; and in each case, I am nothing short of fortunate to have ended up on the good side of luck.

But I didn’t learn my lesson.

Last week, I hung my clothes on the clothesline in Bruce and Peggy’s backyard; it was a big load and would take the entire day to dry—it had been raining for hours without a bead of sun, which had as of late uncharacteristically gone into hiding. After hanging the clothes, I turned around and retreated back into the flat, thinking nothing of it until the next morning, when I needed to dress. Expecting to see two pairs of pants—one of which is my sole gym pair—several shirts, sports bras and socks still hanging on the clothes line, I am surprised, not shocked, to see only a few pairs of socks and the sports bras hanging from the clothes line.

Thoughts run through my mind like lightning: did Peggy take them off already? Can’t be; this is a woman, who, at first meeting, said, “The flat is yours,” in her confident bordering on aggressive tone, “as long as you don’t expect me to do your dishes or wash your clothes.” No way she would have taken them, I think. Besides, why would she take most of the clothes and only leave a few? Clear-cut case of robbery, I concede to myself. I rush to Brucie’s back door. He opens it, alarmed at my urgency.

“Brucie, I left my clothes on the clothes line yesterday, but most of them are gone,” I say, hoping he somehow has the answer I yearn for. “Did you take them off the line, by any chance?” My face contorted into a hopeful shape: eyebrows arched, eyes docile, lips parted. Even before I could brace myself for the answer, though, his face gave him away.

“I’m ‘fraid not, lovey,” he said, already having realized it was the thieves in the night.

Over the next two days I would find out that not only were my clothes, which were, by now, rather tattered, missing from the house, but also a wheelbarrow and a suitcase of old clothes kept in a shack on the property.

“Now that I think about it,” I say, the sun diligently watching over me, “I do remember a dog barking for at least a half hour last night, and even a silhouette walk by my window.” Brucie pauses, sleuthing the scene like Dick Tracey (Brucie’s last name is, by comedic yet in his childhood traumatizing, I’m sure, coincidence, Dick). His head spins from one ear to the other.

“Impossible,” he says matter-of-factly. “They didn’t come from that way—they must have climbed over one of these fences here.” He points to two of the four fences enclosing his home; tall enough to deter a dog, a child, a resident, but not a thief.

“When was the last time this happened, Brucie,” I ask, trying to gage what kind of constant threat he lives under.

“About five years ago, but you never know.”

“I’m sorry your clothes were stolen,” Peggy sympathizes with me later before she hands me a verbal spanking. “But you mustn’t forget, lovey, This Is Africa.”

You can say that again.

Tears of JoyYou never know what you will learn from a child. Likewise, I never imagined what I would hear last Friday when, after talking about journalism as storytelling and the journalist as an artist who must ask questions not only of others but of herself, I asked the children to, out loud—and captured with the beauty of an instrument that seizes the intricate detail of time, place, and emotion like no other, a FliP video camera—answer me questions about themselves.

These are half of the grade five learners, as they call students in South Africa, at the Lilydale Higher Primary School in Soweto, the country’s most renowned area. Soweto, now the size of a small urban forest, was formerly a township whose name remains synonymous with anti-apartheid demonstrations and the heinous police brutality that followed in the 1976 Soweto uprisings, with Nelson and Winnie Mandela’s home in Orlando, and with the signing of the 1955 Freedom Charter in Kliptown—all helping to reinforce the importance of the district at the onset of democracy in 1994.But many parts of Soweto, including Dlamini, where Lilydale is situated, and Kliptown—the squatter camp just across the river where many of Lilydale’s students live in squalid conditions without heat, electricity, or proper housing—remain not only underdeveloped, but neglected. Many of the children who sit before me during after-school training have never eaten more that one meal a day, never ridden in a car, and never seen a miniature video camera before, let alone owned and operated a modern laptop such as the XO.I soon find out what else these resilient children have been deprived of at such a tender age.

“What makes you happy,” I ask, my voice hidden behind the camera, a protective shield providing me the license to ask anything I want.

Arms shoot through the empty air like rockets, swaying back and forth until I point the spotlight of the camera on them.

“Seeing my little sister smile,” says Phumelele, the pretty 10-year-old girl who, with her big brown eyes and everlasting smile, never ceases to amaze me.

“OK,” I say, quickly shifting the camera’s gaze to the next fame-hungry learner in the room. “Who else?”

“Singing,” shouts a girl in the front of the class.

“Dancing,” another voice rings out. I try to capture them all, my camera arm spinning in circles around the room.

“Now write your answers down on the XOs as you think of them,” I urge the youngsters. “These are your projects and we want to remember your answers.”

But once the responses begin rapidly deviating from things that make the learners happy to what they want to be when they grow up, I decide to shift the mood of the session.

“And what makes you sad?”

Silence envelops the room like an invisible cloud.

One learner, a light-skinned plump girl in the back, confidently raises her hand. She wants to be heard, but she struggles with the words.

“When people bully my brother,” she says. The camera’s fixed, unflinching gaze on her bids her to continue. “And when people discriminate against me.” Her face grows slightly pink.

“Discriminate against you,” I begin surprisingly, hoping she won’t lose her urge to share, “what do you mean?”

“When they call me names, like I’m fat.” Painful jitters come from across the room. The girl sinks in her seat, less mortified than she is regretting of having spoken. I intervene.

“Guys, no one should be laughing. This is very private and personal stuff that learners are telling us, so we should respect that. Is everyone typing this on the XO?”

With heads buried in their keyboards, fingers typing, and more hands erecting themselves each second, I come closer to the plump girl with thick braids.

“Thank-you,” I mouth to her, pleased her answer has incited others to raise their hands.

I will never forget what happened next.

“So what makes you sad,” I repeat to the class.

Completely unrehearsed, unscripted, unintended, and unexpected, came truth—beautiful, painful, evocative, truth.

With the camera as my microphone and their license to speak, I slowly walk around the room and learn about the devastation these children had been through, either through their own or relative experience.

“When my mother dies,” says a boy. I look at him speechless, the only transition to the next moment coming from interruptions from the rest of the class.

“When they hit or abuse me,” says another. I had no time to think. Tears swelled in my eyes. I fought back the emotion.

Phelo, Phumelele’s shyer other half, fights for my attention next. The flip gives it to her. She pauses when she realizes the time is hers. Instinctively, I zoom in.

“When my mother doesn’t pay enough attention to me.” Her eyes pierce mine through the camera, seemingly forever.

I know this girl; she isn't a stranger. It hurts me to think about the conditions she comes home to. I have to keep moving the camera. It lands on another girl near Phelo.

“When you lose a baby,” she says to more crackling laughter.

“You mean when someone loses a baby,” I say.

She nods.

“Make sure you guys are writing this stuff down,” I say before telling them a story about when I was young and got invited to a birthday party where no one liked me. In the middle of the night, I tell the attentive learners, some of the girls pour popcorn all over my head.

Retelling the story is more difficult than reliving the episode.

Everyone goes through pain, I say; it’s the way we react to the difficulty in our lives that makes us who we are. I think of the kids; battery, neglect, sexual assault, and poverty flash before my eyes. Realizing an hour has already passed and I have to conclude my session, I decide to offer the brave, resilient learners in front of me the only thing I can: hope.

“I want you to remember that you all can be whatever you want to be and do whatever you want to do.” They watch me, waiting. “And if you ever want to talk, please come to me. I love each and every one of you.”

After every XO is turned off and stacked neatly in groups of five on the teachers desk and as I watch 40 of the most intimate people I’d met pile out of the classroom and into the arms of waiting friends outside, I realize that was the fastest ‘I love you’ I ever meant.

As I lie here and type, miles away from Dlamini in another South African life in Cape Town and a few hours from my ascent into the skies and descent into Boston, their playful laughter still rings in my ears, their loving eyes still carry me home.

A GiftThe next day, Phelo gives me a card. It is a paper folded into the shape of an envelope, with colorful writing on it:

To: OleFrom: PheloI wait until I am alone to open it. On different sides of the paper, almost like a verbal origami, it reads:

You are the best. You are sweet than honey. You are stronger than a lion.Dear Ole: Thank-you for your hard work for teaching us so much about the XOs. I wish you would not go back but a visit is not for a long time. I will surely miss you all. May you be blessed with good ways.PoemWhat is a home? A home is where the heart is. No matter no poor no matter how rich, you’re always blessed from above.On another smaller piece of paper, in pencil as opposed to pen, she writes:Note pleaseIf my drawing is good please make me a superstar or an artist in America. Please.The last item in the envelope is a paper cell phone with her phone number. What a treasure.

The Joke’s On YouA lighter side of South Africa: a literary composition of jokes ranging from Kliptown to Meredale.

Olesia: What do you call a white person in Kliptown?

Nomsa: A tourist.

Brucie: Do you know why they call them ostriches?

O: No, why, Brucie?

Brucie: Because they lay eggs so big, it’s an ass—stretch.

Peggy: O, have you seen our national flower?

O: No, where is it?

Peggy: Oh right there, hanging from the tree.

I see a plastic bag.

Brucie: So an elephant and a camel are having a conversation and things get a little heated. They start calling each other names and the elephant says to the camel, “nice tits on your back.” The camel retorts, “yeah, well, at least I don’t have a dick for a mouth.”

Brucie: After the Zimbabwean war of independence in 1980, many white Zimbabweans moved to South Africa, where they continued to enjoy many luxuries they could no longer reap in their own country. We South Africans used to call them ‘wenwes’ because they would always talk about their privileges in the country back when it was Rhodesia and whites had all the power. They would say “when we this…” and “when we that…” After the end of apartheid in this country, though, we called them the ‘Soweto’s’ because now they said, “so where to now?”

One day I was talking to Peggy and Bruce, and something inflammatory came up. Brucie started talking. Peg interrupted.

Peggy: Brucie, you better watch your mouth or she’ll broadcast it t the world on that blog of hers.

I must have turned a shade of crimson. And remained speechless.

Man that walks into Nomsa’s house: Hi.

O: Hi, who are you?

Man: I’m a cop, but don’t worry—not the corrupt kind.

I laugh. He asks Nomsa for something and leaves.

O: Nomsa, what did he want?

Nomsa: Oh, just weed.

The Last 24 African HoursCape Town may be the most stunning city on earth. It represents a world of jagged rock and majestic greenery; a land of breaking waves, fluttering birds, and hovering clouds. It is a place more than 80% of South Africans have never seen. Home to tourism and real estate, the city has as many whites as it does blacks, although as in the rest of South Africa, blacks are poor, whites are not. But unlike in the rest of South Africa, the whites here, at least aesthetically to the naked eye, seem materialistic, pretentious, ignorant. Gucci sunglasses and blonde hair are staple sights in this city, the disparity between the whites and blacks less evident because you hardly see the blacks. This is white South Africa, a world away from the worries of Kliptown.

I am staying with a friend of a friend, a Nick. He is funny, kind, welcoming, and smart. But he doesn’t lie. We start to talk about racism in the country, division in the country, corruption in the country.

“When either you or your friend, or family member, your coworker, someone you know, has been robbed or mugged, or even killed during a robbery, you can’t help but turn hateful and become a little bit racist,” he says before remembering a time him and his friends fell asleep at a cottage in Durban only to wake up to shattered glass and empty pockets.

“They stole everything,” he says as we take in the indescribable beauty of the Atlantic Ocean’s waves breaking against rocks on our right and multi-million dollar condos in front of Table Mountain on our left. “I was pissed.”

That was kind of like the time he awoke to shuffling noises at his house and saw a man hovering over him, holding his cell phone and muttering he was going to kill him. It was also similar to the time his car was broken into.

Regardless the color, every South African has a story; unfortunately, it’s usually one of angst against ‘the other.’

I leave to Jo’burg tomorrow, to Boston tomorrow.

This journey has left me exhausted. Changed. Learned. Better. Affected. Timeless.

Thank you for sharing. Thank you for reading. Thank you for the emails. Thank you for being here.

Media to come soon.