Saturday, September 5, 2009

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Inscription Inside the Pages of 'Long Walk to Freedom', My Gift to the Girls

Monday, August 17, 2009

...Learner Training, Parent Meeting, Power Outage, Confinement, Thieves in the Night, Tears of Joy, A Gift, The Joke’s On You, and The Last 24

“Of course we can make that happen,” I responded in a haste gasp, barely catching my breath or noticing if I had interrupted him. “That’s precisely what we are here to do, Mr. Jacobs [the Soweto District Director from the Gauteng Department of Education]. We are hoping that the Lilydale deployment goes so well that we’ll be able to expand this program to schools, ideally, all over the country.”

“Good,” he said, as if I delivered the desirable answer he was anticipating. “I want to bring the XO to Soweto; have the entire district full of them. I want to move on this fast.”

I couldn’t believe my ears; was it really this easy?

“Then lets move,” I said without skipping a beat. “I will email you and your team,” who had, by this point, noticed an important meeting—their input could cost them a raise, a lack of it their jobs—occurring on the podium and, after meeting my gaze, made certain to pull up a few chairs next to the Director and I while Phindile assisted Nastya and John with the remainder of the grade 5 enrollment list, “tonight and get in contact with my OLPC Corps manager to discuss specifics such as costs. But tell me, how many XOs, or schools, are we talking here?”

The diversion of his eyes from mine and into an empty stare directed at the ground coupled with his delayed conversation indicated he had begun counting numbers in his head. The sun bounced on and off his thin glasses as I waited, momentarily taking a minute to glance at the jubilant cheers of learners rejoicing once a classmate was handed their very own boxed XO, the sharp edges of the cardboard box reminiscent of bountiful Christmas presents these children have likely never gotten.

“Roughly 13,000,” he said nonchalantly. “All the primary schools in Soweto.”

“What happened in Rwanda,” I said, wasting no time, “is that the Ministry of Education held multiple structured training seminars with all the teachers who would be involved in the multiples of schools at the forefront of deployments across the country. They also trained technical staff to ensure they could work more efficiently and independently of outside parties to strengthen sustainability. In addition, certain subject-specific modules were created to integrate the XO into the classroom.”

I was breathless. The sun bounced from head to head on the front podium row, off the District Director’s glass lens, and into my eye. I had positively overwhelmed him. One of his co-workers, an ever-smiling, nurturing woman named Lizzie, took the lull in voices to pick up where I left off.

She leaned forward, masking the pitch of her voice to ensure she wasn’t in competition with John and Nastya, who by then had barely reached labeling and distributing computer #20. “I think,” she almost whispered, “that we should invite them to the Gauteng Department of Education meeting in a few days so they can impress this idea on all the District Directors in the municipality.”

Irritated, Mr. Jacobs shot Lizzie a stiff glance and very slowly said, “That’s exactly what I don’t want.”

Lizzie and I, both finding ourselves in a forward-leaning position, automatically retracted our bodies at the sound of Mr. Jacobs’ surprising proclamation.

He continued. “I want Soweto to have this project first, and then when the rest of the District sees the laptop here, they will want to follow suit.”

With the exchange of a knowing look between us as brief as a bolt of lightning, Lizzie and I understood that the District Manager wanted the glory of an XO success story in his own Soweto jurisdiction—historically and presently one of the most disadvantaged areas in the Gauteng municipality—all three to set a precedent with the Municipality and the Federal government, ensure Soweto kids were reaping the benefits of a transformative, unique 21st century education, and take ownership of the project in Soweto in case the Gauteng Department of Education didn’t want to jump on board. Everyone has ulterior motives, I thought, but if his included offering youth who live in squatter camps, who are physically abused at home, and who will never imagine their lives to be silently interrupted by the four-letter killer in the next decade the tools to think differently about their circumstances and the potential to change them, then so be it.

“I understand,” I replied, faintly hearing Nastya and John begin calling out numbers in the 70’s. I quickly recalled Mr. Mohamed, upon introducing us to Mr. Jacobs, mentioning that the District Director, obviously a very busy man, could only make a brief appearance at the launch and that he would have other responsibilities to adhere to afterwards. I had to move. Directing my gaze at all three Lizzie, Mashooda—a young, tiny Indian woman who had also pulled up a chair next to the Director and I but had been relatively silent throughout the hasty discussion—and Mr. Jacobs, I concluded the conversation: “My group and I are absolutely thrilled that you are this invested in a much larger-scale XO deployment in Soweto and we’re very committed to working with you during the next few weeks so that this project can really see the light of day.” Now, setting my sights more at Mr. Jacobs’ administrative personnel who would try, as we earlier discussed, to raise money from corporate sponsors and contact the Gaunteng’s E-learning Director in hopes of garnering an ally in a key sector while Jacobs put his authoritative backing behind the project, I decided the XO could do the rest of the talking for me.

“I will put you in contact with our project director, Paul Commons, who will facilitate more serious discussions from a senior OLPC standpoint and maybe next week we could meet at the Department to discuss particulars. Would you mind typing your email addresses in this write file on the XO, please?”

They smiled and cautiously moved over to the little machine with a big mission and began, carefully pressing their fingers on the green rubber keys, to type their contact information. The students looked on in wild amusement.

Learner Training

Upon completion of teacher training mid-July, as a group comprised of me, John, Anastasia, and Lilydale’s entire teaching staff—including the principal—we agreed that learner training would take place Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays after school for two hours. The 87 learners would be divided into groups of three and trained by John, Nastya and I in three classrooms next to one another. The training would occur for two weeks, after which we would use the same rooms, times, and days, to continue familiarizing the learners with the XO during an after school program that would be less structured in terms of learning the XO and instead focus on the students learning about themselves, using XO programs like write and record. This would indeed be the practical implementation of the student journalism proposal for which my team and I were awarded one out of thirty spots in the OLPC Africa Corps.

And so, precisely at 2:30 PM on Wednesday, July 22nd, approximately two hours after the end of the launch, learner training began. All XOs were numbered and charged and, after Phindile distributed laptops 1-89, children whose excited screams, shouts, and laughs infected the halls of the school more potently than a biological bomb, quickly filed into the classrooms, divided into three groups. Turned out I got the rowdiest bunch.

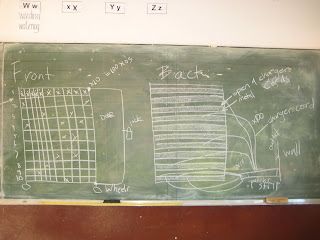

Each one of our training styles was unique to the person leading it. While John took a relaxed and reinforcing approach by allowing the learners the freedom to roam and experiment on the XO before instructing them and Nastya took a more structured method by using the chalkboard—which could barely contain the thousands of words pouring from it from the previous lesson—to demonstrate how to use programs such as write and scratch, I began my training the only way I knew how: with the basics.

Introducing the children again to me and my group and explaining the reason why we had so frankly impeded their usual schedule of euphoria and freedom at the sound of the last bell of the day, I told them that we were Americans working with the Kliptown Youth Program and Lilydale to help spread computer literacy and a more inclusive kind of education to the grade 5 classes at the school. The computer was made for kids, it’s got loads of both fun and educational programs installed on it with the capacity to install more with the help of the server, and it’s got mesh networks that allow you to chat with your friends, I said to a sea of wide-eyed 10-year-olds who intuitively somehow knew that chat was just another deviant of fun. I continued on with battery installation, powering the XO on and off, personalizing the laptop with the entry of your name, individual color, and talking about the programs, none of which the kids cared more about than the .ogg music files found hidden beneath obscure titles in the browse function and games such as maze and implode, although the ‘speak’ man’s digitized, monotonous, terminator-like voice came in as a close—and annoying—second in disrupting both my students and I during not only the first, second, and third, but fourth and last training sessions. In the two hours I had on that first training seminar, I set a solid foundation for the rest of the sessions, especially because I managed to begin actively explaining about the navigation of the laptop, including the ‘border’.

The second, third, and fourth seminars consisted much of the same plan in terms of laptop training, divided into a daily break-down of the day’s activities on the board, review from last class followed by questions, and usually two or three educational programs like scratch, write, record, wikipedia, moon, and read for the students to familiarize themselves with before I broke down and capitulated to relentless shouting—and polite requests coming from adoring eyes—to play “GAMES”!

However, the three sessions following the initial training did not go according to plan; practical issues such as the charging, transport, and storage of laptops—despite being discussed at length during teacher training—caused problems for reasons that could only unveil themselves during the application of such activities.

After training on the first day, laptops in all three classes had to be put away into the administrative building until a more permanent solution was found. But to relocate the laptops day after day following training seminars from classrooms adjacent to the administrative building would soon prove to both compromise the security of the laptops and make for very difficult and ineffectual XO inventory counts. About 20 minutes prior to the conclusion of the first training seminar, John, accompanied by a quiet knock, came into my room.

“We are going to finish up right away and begin putting the XOs back,” he said, watching my face for approval. My silence bade him to continue. “So I’m going to start calling numbers 1-10 right now and if you have any of those learners you can send them out to the courtyard,” he said, pointing to the open space behind him, “and I will put the laptops into boxes. We’ll do that in intervals of 10 until we reach 89.”

“Sounds good,” I said in a hurry, eager to get back my kids, who were, this excited and close to the end of the school day, beginning to summon chaos. “I’ll send out my 1-10’s right away.”

By simple virtue of the division of XOs into three groups, there was no semblance of order or sensibility in the devised system—that would become apparent in the minutes that followed.

My class contained no learners in the first batch, only a few in the second, many in the third, and a multitude of learners dispersed between intervals 40-89. Each time I called for the next group, the class would, already having lost focus of the XO because I taught them to shut it down in anticipation for its storage, begin to stand, move around, ask for permission to go the bathroom, and request to be let go, all things I had to avoid in order to make sure no XOs were stolen in the frenzy of the situation. In total, it took more than 45 minutes and many frazzled nerves to tally all the XOs and carry them back to the admin building to be charged, which was a problem in itself, as even with multiple power strips and several plugs, not all 89 XOs—11 were given to teachers—could be simultaneously plugged in at once.

The next day after school, with the grade 5’s swarming around their respective classrooms while the grade 6’s and 7’s gave us disdained looks, my group and I decided to take a more organized approach to the storing of laptops. This time, instead of being given learners whose numbers were all over the place, we decided to order the learners in ascending order, with me having the privilege of training learners who were assigned laptops 30-60. From now on, before beginning training, each member of my team would count the laptops entering their class, mark which learners were absent, distribute the laptops, and ensure the number of laptops left in the class after the departure of the learners corresponded to the initial figure. But since all the laptops couldn’t be charged the first day, the first hour of training on the second day was compromised and had to be utilized without laptops. I took this opportunity to get to know the kids who would soon bring tears of joy to my eyes in my most sincere and evocative African moment yet, and tell them about OLPC.

I told them about OLPC’s mission of granting a 21st century education to children who would never have had the opportunity otherwise. I told them that children who were maimed in Sierra Leone and the Congo due to extensive civil war were also using the XO at the same time to learn how to express themselves the same way we were going to do next week, a statement acting as a prelude to my next question.

“Do any of you know what journalism is,” I asked, pleasantly surprised at the speed arms began floating in the air. A pretty girl with braided hair raised her hand for the first but certainly not last time. I would soon find out her name was Phumelele, and she would become one of the smartest and most eager students I would have. With confidence and poise seldom found in a girl that age, she began to speak.

“Journalists,” she said, “write stories.”

Brief yet accurate to a tea, I concurred with her. “Yes,” I said, pleased at her courageous intellect, “and it’s never too early to start writing stories about yourselves.” Realizing I had the undivided attention of the class, I wasted no time. “Other than to teach you about the XO, we are here to help you learn about yourselves and each other. Next week we will begin that project using write, record, and maybe the internet if it is setup by then.” At the mere mention of that word, the class erupted into enthusiastic whispers, at which point I had to quell their hopes.

“But we don’t have internet yet, so let’s continue with the training. Who wants to help me carry the XOs into class?”

Running towards me with a look of perpetual Christmas in their eyes, I had now to choose three volunteers from dozens of buzzing kids.

Parent Meeting

After approaching Mr. Mohamed with the idea of meeting with parents of the learners involved in the Lilydale OLPC project during one of our first conversations with him, Mr. Mohamed drafted a letter that requested the presence of all grade 5 parents at Lilydale on Saturday, August 1st, to inform them of the project and create an awareness around the XO that could potentially foster joint ownership in the future and mitigate security concerns.

As the first rain in months fell hard and fast from every corner of the dismal grey sky above us, that first day of August we drove into the Lilydale parking lot, taking curious notice of the very few cars and people surrounding us.

“Hurry up,” Mr. Mohamed’s accented voice sprang from inside the administrative building, his arm motioning us forward. “The meeting is across the yard.”

We were taken to a room full of approximately 15 people, mostly women—or mothers—of the total 89 learners in the grade five class. Whether or not the rest of the guardians decided to forfeit the meeting because their children did not deliver the alert, because it fell on an early 1st of the month, or because the weather was reminiscent to Noah’s Arc, it didn’t matter; here were 15 parents eager to learn about the ‘school in a box’.

After a lengthy introduction about OLPC, the XO—which was, at this point, being passed around from one astounded parent to the other—and the policies associated with the program, we were met with a cacophony of crickets after asking the parents if they had any questions or comments. After a few minutes pause, one lanky woman with a leather jacket and a white knit hat stood up.

“I want to thank-you, your NGO, and the man who used to go to this school and is now the Director of KYP for bringing these laptops for our children,” she said slowly, pausing after each passing word so as not to fumble her appreciation. “When my daughter came home every day last week, she just couldn’t stop talking about the laptop and said she even finished some of her homework for class using the computer. She is so happy and so are we.”

Murmurs of gratitude reverberated from the crowd to us and vice versa. But the lady in the leather jacket had a more important point to make.

“Is there any way that the children could take home the laptop? Or, if not, if they can be purchased individually?” Before we had a chance to dart our eyes—which harbored a look of inability to single-handedly answer the question—to Phindile and Mr. Mohamed, both of whom had expressed their disapproval at joint-ownership because of security and trust concerns, she concluded her statement and took back her seat. “We don’t have a lot of money, but we would do anything for our children’s happiness.”

We regretfully explained that although joint-ownership is an integral part of the OLPC program because it not only allows the learner to take incentive and excitement in their own learning, but multiplies the potential of the learner by allowing unhindered, private access to the tools on the XO, we were neither experts or locals in the community and had to heed the advice of our Lilydale partners, who could possibly still allow learner ownership once efforts at increased community awareness were in place and the learners showed a dedicated responsibility towards the XO.

As the meeting concluded and the parents signed their names next to their children’s on an attendance list at the front of the room, the XO’s record function capturing the movements of the crowd elicited ecstatic oooh’s and aaaah’s.

Power Outage

One sunny morning a few weeks ago, Brucie intercepted my daily breakfast of oatmeal, yoghurt, and tea to tell me a story—well, a couple stories. What started as a discussion about post-apartheid South Africa—business that lost human capital when, because of the active enforcement of affirmative action laws, (officially called Black Economic Empowerment) skilled whites were fired to make room for semi-skilled blacks—ended with an explanation about a national problem that, at least by the initial sounds of it, has little do with color: electricity. Ignoring warnings that came in the mid-80’s and perhaps even earlier about a looming electricity crisis, South Africa’s top industry leaders and politicians faced a rude awakening during the dawn of a new democratic era whose lack of planning threatened to eclipse the humanitarian gains of the post-apartheid era. To avoid serious electricity problems in the most affluent country on the continent would necessitate either the building of more water dams, wind turbines, or the extraction of more coal, all of which options were either unexhausted or untapped ten years ago. Today, regardless of what skin color one was born with or the relative prestige in which one lives, the whole of the South African population is reminded that electricity remains a scarce commodity, stretching from daily TV warnings similar to American ‘Amber Alerts’ or ‘Terrorist Threats’ to entire days without power—a reality we had to for several days confront last week at Lilydale when we were forced to forego XO-classroom integration on Monday and Tuesday.

Confinement

[Editors Note: On a short break from reading Hunter S. Thompson’s ‘Kingdom of Fear,’ I’ve decided to take a more ‘gonzo’ approach to my writing; brisk, blunt, and fearless, I will emulate his indefinable style in an effort to find my own. ‘Long Walk To Freedom’ inspired me in much the same way and honed my use of descriptive metaphor.]

[Read at Own Risk.]

It is neither pleasing nor easy being stuck in one of the most beautiful and historically rich countries on earth with no money, no plan, and all the time in the world; although it allows for more ample reading, writing, and introspective time, it downright sucks and after countless hours and endless days, provides for one of the most regrettable activities ever. Despite undignified, prolonged begging from the University of Massachusetts Boston, we were given no grants and no pity for this project. As a result of little additional funding on top of the $10,000--$8,500 of which was used on plane tickets—very generously provided by OLPC, my group and I have lived a limited reality for the last several weeks. On top of being activity-less—there is much time left over after leaving Lilydale, during the afternoons, and those popular three-day breaks I’ve come to loathe: weekends—the three of us are living in a small—yet comfortable and nothing to scoff at—flat with a shared bathroom and competing personalities. In an effort to escape perpetual confinement—of body, soul, and mind, you bet—and flirt with life just a little, I a few weeks ago decided to get a month-long membership at the plush, amenity-full gym across the street: the always bustling, ever-modern, never-dirty, Virgin Active.

It is in these two hours that I can listen to music, sweat intensely, and, in a carefully rehearsed speech, explain who I am, where Boston is, and what on earth I’m doing with a one-month ticket to fitness in the middle of South Africa’s most intimate ‘township’. My trainer, Lucas, a young Xhosa guy with rock-hard abs and a steely work ethic, often times acts as my new best friend; we’ve even started training together and doing the repulsed by some, envied by all, fist-punch.

“Sorry I’m late,” he says to me with his characteristically big brown eyes and uniform smile as he sits next to me on the stretching mat in workout gear. “How was your day?”

Although I’ll answer in short, Lucas—or any other human being who is not my parent, lover, best friend, or hairdresser—will never get the full story of what’s going on inside that thick head of mine or the consequent feelings inside the deepest bowels of my beating heart.

“Are you going to tell me what’s wrong,” he asks for the second day in a row, waiting patiently for an answer that may offer a morsel of truth, unlike yesterday’s “it’s no big deal” response.

Everybody knows that posing such a loaded question such as ‘How are you,’ or ‘How was your day,’ to a complete—well, almost complete; he has seen me sweat—stranger is only a polite formality that the questioner never really wants answered but rather expects a bland, monotonous reply to. But since he is a good, honest man (he’s only charging me half price, 50 Rand, per hour), I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt: Even if he was interested in my rambling about my metaphysical inability to transgress the physical barriers preventing me from roaming my mind and the vast valleys of the Transvaal (the former term for the municipality of Gauteng) that I’ve read about with salivating, vivid envy in ‘A Long Walk to Freedom’, it wouldn’t be right to unload on poor Lucas. Besides, I don’t feel like talking about it; being at the gym has pacified my nerves and (temporarily) palliated my confinement. Live in the moment, I tell myself.

“Nothing, Lucas, really,” I half-lie to him. He knows I’m holding something back but he doesn’t poach—I knew he didn’t want the burden. “So we doing 10 speed and 1.5 incline for another dreadfully revitalizing 12 minutes today, Lucas?”

His smile warms my senses and palpitates my heart. Time for the death run.

Two hours have passed and I am drenched in sweat. I bid Lucas goodbye and thank him sincerely for yet again kicking my ass. I feel good—but not as good as I’m about to feel when I step into a luxury known all over Canada but surprisingly less so in the bottomless pit of capitalism itself, America: the steam room. All the women in the steam room—large enough to fit close to twenty standing women, maybe 15 sitting skinnies—are naked. They were yesterday, the day before, and they continue to be today; and so, trying desperately to assimilate to the society I have become a part of, I decided the week before last that I would go naked too.

My parts bouncing up and down, I brazenly tiptoe into the scathing mist, only to be turned back—and on no nice terms.

“We shower before entering the steam,” says a lady who looks like the rest in the steam room, their features barely discernable in the fog that blocks my detailed dissection of my confronter. “See,” she says annoyed, pointing to a sign behind my back. I turn around to read the obvious.

ALL PATRONS MUST SHOWER BEFORE ENTERING THE STEAM ROOM.

Feeling defiant yet aware of fighting a losing battle, I concede to wash myself ‘before entering the steam room.’

Opening the door only slightly and closing it at cheetah-speed so as not to upset any more steam room wardens after my bitter shower, I am blinded by the white steam; all I see behind it is figure-eight silhouettes (be assured there is no shortage of curves in a South African steam room). After literally taking a stab in the dark and climbing over heads and stretching my legs in compromising positions (for the ladies underneath me) to reach the most sought-after spot in the steam room—the top corner, I plop down and am automatically enveloped, tickled, and warmly embraced steam and the calming sound of Zulu gossip. Confinement never felt so good.

Thieves in the Night

Before going on this trip, I spoke to many so-called African ‘experts’ who, despite having had very unique personal experiences in Africa and South Africa and offering me contrary pieces of advice, all warned me that no matter what I would or would not live through, what I would or would not have not seen, how long I had been in the country, or how comfortable I could have possibly felt, to never, ever, ever, they repeated, let my guard down.

Well, I did. I let it down when I felt that, after living amongst alcoholics, beggars, cheaters, abusers, addicts, thieves, children, teenagers, medicine women, Rastafarians, community workers, pioneers, and extraordinarily good people in a slum in one of the most crime-ridden countries on earth, I could survive not only anything, but everything and everyone, and forgot to put my iPod away. I let it down when I walked home alone from the field I used to run at in Kliptown. I let it down when, after being stranded at the gym one night, I allowed one of the managers to drive me home after dark. There must have been other times my common sense eluded me for instinctual spontaneity and chance; and in each case, I am nothing short of fortunate to have ended up on the good side of luck.

But I didn’t learn my lesson.

Last week, I hung my clothes on the clothesline in Bruce and Peggy’s backyard; it was a big load and would take the entire day to dry—it had been raining for hours without a bead of sun, which had as of late uncharacteristically gone into hiding. After hanging the clothes, I turned around and retreated back into the flat, thinking nothing of it until the next morning, when I needed to dress. Expecting to see two pairs of pants—one of which is my sole gym pair—several shirts, sports bras and socks still hanging on the clothes line, I am surprised, not shocked, to see only a few pairs of socks and the sports bras hanging from the clothes line.

Thoughts run through my mind like lightning: did Peggy take them off already? Can’t be; this is a woman, who, at first meeting, said, “The flat is yours,” in her confident bordering on aggressive tone, “as long as you don’t expect me to do your dishes or wash your clothes.” No way she would have taken them, I think. Besides, why would she take most of the clothes and only leave a few? Clear-cut case of robbery, I concede to myself. I rush to Brucie’s back door. He opens it, alarmed at my urgency.

“Brucie, I left my clothes on the clothes line yesterday, but most of them are gone,” I say, hoping he somehow has the answer I yearn for. “Did you take them off the line, by any chance?” My face contorted into a hopeful shape: eyebrows arched, eyes docile, lips parted. Even before I could brace myself for the answer, though, his face gave him away.

“I’m ‘fraid not, lovey,” he said, already having realized it was the thieves in the night.

Over the next two days I would find out that not only were my clothes, which were, by now, rather tattered, missing from the house, but also a wheelbarrow and a suitcase of old clothes kept in a shack on the property.

“Now that I think about it,” I say, the sun diligently watching over me, “I do remember a dog barking for at least a half hour last night, and even a silhouette walk by my window.” Brucie pauses, sleuthing the scene like Dick Tracey (Brucie’s last name is, by comedic yet in his childhood traumatizing, I’m sure, coincidence, Dick). His head spins from one ear to the other.

“Impossible,” he says matter-of-factly. “They didn’t come from that way—they must have climbed over one of these fences here.” He points to two of the four fences enclosing his home; tall enough to deter a dog, a child, a resident, but not a thief.

“When was the last time this happened, Brucie,” I ask, trying to gage what kind of constant threat he lives under.

“About five years ago, but you never know.”

“I’m sorry your clothes were stolen,” Peggy sympathizes with me later before she hands me a verbal spanking. “But you mustn’t forget, lovey, This Is Africa.”

You can say that again.

Tears of Joy

You never know what you will learn from a child. Likewise, I never imagined what I would hear last Friday when, after talking about journalism as storytelling and the journalist as an artist who must ask questions not only of others but of herself, I asked the children to, out loud—and captured with the beauty of an instrument that seizes the intricate detail of time, place, and emotion like no other, a FliP video camera—answer me questions about themselves.

These are half of the grade five learners, as they call students in South Africa, at the Lilydale Higher Primary School in Soweto, the country’s most renowned area. Soweto, now the size of a small urban forest, was formerly a township whose name remains synonymous with anti-apartheid demonstrations and the heinous police brutality that followed in the 1976 Soweto uprisings, with Nelson and Winnie Mandela’s home in Orlando, and with the signing of the 1955 Freedom Charter in Kliptown—all helping to reinforce the importance of the district at the onset of democracy in 1994.

But many parts of Soweto, including Dlamini, where Lilydale is situated, and Kliptown—the squatter camp just across the river where many of Lilydale’s students live in squalid conditions without heat, electricity, or proper housing—remain not only underdeveloped, but neglected. Many of the children who sit before me during after-school training have never eaten more that one meal a day, never ridden in a car, and never seen a miniature video camera before, let alone owned and operated a modern laptop such as the XO.

I soon find out what else these resilient children have been deprived of at such a tender age.

“What makes you happy,” I ask, my voice hidden behind the camera, a protective shield providing me the license to ask anything I want.

Arms shoot through the empty air like rockets, swaying back and forth until I point the spotlight of the camera on them.

“Seeing my little sister smile,” says Phumelele, the pretty 10-year-old girl who, with her big brown eyes and everlasting smile, never ceases to amaze me.

“OK,” I say, quickly shifting the camera’s gaze to the next fame-hungry learner in the room. “Who else?”

“Singing,” shouts a girl in the front of the class.

“Dancing,” another voice rings out. I try to capture them all, my camera arm spinning in circles around the room.

“Now write your answers down on the XOs as you think of them,” I urge the youngsters. “These are your projects and we want to remember your answers.”

But once the responses begin rapidly deviating from things that make the learners happy to what they want to be when they grow up, I decide to shift the mood of the session.

“And what makes you sad?”

Silence envelops the room like an invisible cloud.

One learner, a light-skinned plump girl in the back, confidently raises her hand. She wants to be heard, but she struggles with the words.

“When people bully my brother,” she says. The camera’s fixed, unflinching gaze on her bids her to continue. “And when people discriminate against me.” Her face grows slightly pink.

“Discriminate against you,” I begin surprisingly, hoping she won’t lose her urge to share, “what do you mean?”

“When they call me names, like I’m fat.” Painful jitters come from across the room. The girl sinks in her seat, less mortified than she is regretting of having spoken. I intervene.

“Guys, no one should be laughing. This is very private and personal stuff that learners are telling us, so we should respect that. Is everyone typing this on the XO?”

With heads buried in their keyboards, fingers typing, and more hands erecting themselves each second, I come closer to the plump girl with thick braids.

“Thank-you,” I mouth to her, pleased her answer has incited others to raise their hands.

I will never forget what happened next.

“So what makes you sad,” I repeat to the class.

Completely unrehearsed, unscripted, unintended, and unexpected, came truth—beautiful, painful, evocative, truth.

With the camera as my microphone and their license to speak, I slowly walk around the room and learn about the devastation these children had been through, either through their own or relative experience.

“When my mother dies,” says a boy. I look at him speechless, the only transition to the next moment coming from interruptions from the rest of the class.

“When they hit or abuse me,” says another. I had no time to think. Tears swelled in my eyes. I fought back the emotion.

Phelo, Phumelele’s shyer other half, fights for my attention next. The flip gives it to her. She pauses when she realizes the time is hers. Instinctively, I zoom in.

“When my mother doesn’t pay enough attention to me.” Her eyes pierce mine through the camera, seemingly forever.

I know this girl; she isn't a stranger. It hurts me to think about the conditions she comes home to. I have to keep moving the camera. It lands on another girl near Phelo.

“When you lose a baby,” she says to more crackling laughter.

“You mean when someone loses a baby,” I say.

She nods.

“Make sure you guys are writing this stuff down,” I say before telling them a story about when I was young and got invited to a birthday party where no one liked me. In the middle of the night, I tell the attentive learners, some of the girls pour popcorn all over my head.

Retelling the story is more difficult than reliving the episode.

Everyone goes through pain, I say; it’s the way we react to the difficulty in our lives that makes us who we are. I think of the kids; battery, neglect, sexual assault, and poverty flash before my eyes. Realizing an hour has already passed and I have to conclude my session, I decide to offer the brave, resilient learners in front of me the only thing I can: hope.

“I want you to remember that you all can be whatever you want to be and do whatever you want to do.” They watch me, waiting. “And if you ever want to talk, please come to me. I love each and every one of you.”

After every XO is turned off and stacked neatly in groups of five on the teachers desk and as I watch 40 of the most intimate people I’d met pile out of the classroom and into the arms of waiting friends outside, I realize that was the fastest ‘I love you’ I ever meant.

As I lie here and type, miles away from Dlamini in another South African life in Cape Town and a few hours from my ascent into the skies and descent into Boston, their playful laughter still rings in my ears, their loving eyes still carry me home.

A Gift

The next day, Phelo gives me a card. It is a paper folded into the shape of an envelope, with colorful writing on it:

To: Ole

From: Phelo

I wait until I am alone to open it. On different sides of the paper, almost like a verbal origami, it reads:

You are the best. You are sweet than honey. You are stronger than a lion.

Dear Ole: Thank-you for your hard work for teaching us so much about the XOs. I wish you would not go back but a visit is not for a long time. I will surely miss you all. May you be blessed with good ways.

Poem

What is a home? A home is where the heart is. No matter no poor no matter how rich, you’re always blessed from above.

On another smaller piece of paper, in pencil as opposed to pen, she writes:

Note please

If my drawing is good please make me a superstar or an artist in America. Please.

The last item in the envelope is a paper cell phone with her phone number. What a treasure.

The Joke’s On You

A lighter side of South Africa: a literary composition of jokes ranging from Kliptown to Meredale.

Olesia: What do you call a white person in Kliptown?

Nomsa: A tourist.

Brucie: Do you know why they call them ostriches?

O: No, why, Brucie?

Brucie: Because they lay eggs so big, it’s an ass—stretch.

Peggy: O, have you seen our national flower?

O: No, where is it?

Peggy: Oh right there, hanging from the tree.

I see a plastic bag.

Brucie: So an elephant and a camel are having a conversation and things get a little heated. They start calling each other names and the elephant says to the camel, “nice tits on your back.” The camel retorts, “yeah, well, at least I don’t have a dick for a mouth.”

Brucie: After the Zimbabwean war of independence in 1980, many white Zimbabweans moved to South Africa, where they continued to enjoy many luxuries they could no longer reap in their own country. We South Africans used to call them ‘wenwes’ because they would always talk about their privileges in the country back when it was Rhodesia and whites had all the power. They would say “when we this…” and “when we that…” After the end of apartheid in this country, though, we called them the ‘Soweto’s’ because now they said, “so where to now?”

One day I was talking to Peggy and Bruce, and something inflammatory came up. Brucie started talking. Peg interrupted.

Peggy: Brucie, you better watch your mouth or she’ll broadcast it t the world on that blog of hers.

I must have turned a shade of crimson. And remained speechless.

Man that walks into Nomsa’s house: Hi.

O: Hi, who are you?

Man: I’m a cop, but don’t worry—not the corrupt kind.

I laugh. He asks Nomsa for something and leaves.

O: Nomsa, what did he want?

Nomsa: Oh, just weed.

The Last 24 African Hours

Cape Town may be the most stunning city on earth. It represents a world of jagged rock and majestic greenery; a land of breaking waves, fluttering birds, and hovering clouds. It is a place more than 80% of South Africans have never seen. Home to tourism and real estate, the city has as many whites as it does blacks, although as in the rest of South Africa, blacks are poor, whites are not. But unlike in the rest of South Africa, the whites here, at least aesthetically to the naked eye, seem materialistic, pretentious, ignorant. Gucci sunglasses and blonde hair are staple sights in this city, the disparity between the whites and blacks less evident because you hardly see the blacks. This is white South Africa, a world away from the worries of Kliptown.

I am staying with a friend of a friend, a Nick. He is funny, kind, welcoming, and smart. But he doesn’t lie. We start to talk about racism in the country, division in the country, corruption in the country.

“When either you or your friend, or family member, your coworker, someone you know, has been robbed or mugged, or even killed during a robbery, you can’t help but turn hateful and become a little bit racist,” he says before remembering a time him and his friends fell asleep at a cottage in Durban only to wake up to shattered glass and empty pockets.

“They stole everything,” he says as we take in the indescribable beauty of the Atlantic Ocean’s waves breaking against rocks on our right and multi-million dollar condos in front of Table Mountain on our left. “I was pissed.”

That was kind of like the time he awoke to shuffling noises at his house and saw a man hovering over him, holding his cell phone and muttering he was going to kill him. It was also similar to the time his car was broken into.

Regardless the color, every South African has a story; unfortunately, it’s usually one of angst against ‘the other.’

I leave to Jo’burg tomorrow, to Boston tomorrow.

This journey has left me exhausted. Changed. Learned. Better. Affected. Timeless.

Thank you for sharing. Thank you for reading. Thank you for the emails. Thank you for being here.

Media to come soon.

Friday, August 7, 2009

Here's To You

Ive learned that I can be bossy

Ive learned that I am very organized, responsible, and demanding

Ive learned that I will stop at nothing to achieve a goal

Ive learned I am easily hurt because my compassion is wounded

Ive learned that without writing, I am confined to a brain of anxiety

Ive learned that Im addicted to creating; without it I feel worthless

Ive learned to take comfort in 40 10-year-olds

Ive learned how powerful is the urgency and plea of the spoken word, how overpowering the secrecy and nuance of the written

Ive learned how pivotal physical exercise is to mental freedom

Im learning there are detriments to ambition

Im learning that intelligence comes as much in the form of dialogue as it does literature

Im learning how much love is in this world and yet how often children are in search of it

Im learning how much I love to read

Im learning to trust no one but myself

Im learning how ignorance imprisons

Im still learning to overcome my fears

Im still learning to think before I speak

Im realizing how talkative and curious I am when I lead a sober life

Im continuing to be amazed at the goodwill of the people in my life—k.a.,a.p.,o.p.,s.p.,k.k.,r.g.,p.o.,h.s.,v.w.,p.l.,b.d.,t.m.,m.m.,b.m.,s.l.,f.b.,a.g.,p.c.,j.m.,d.l.,a.c.,p.r.,j.a.,f.p.,a.a.,l.w., s.f..

Im remembering how big dreams are when you’re a kid

Im continuing to learn that the human experience is so difference it can by virtue never be the same

Im starting to believe that children are the strongest humans on earth

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Transcript of My OLPC Lilydale Launch Speech

July 22, 2009, 9:30 AM

Good Morning!

Principal Mohamed, Lilydale Teachers, Ministry of Education representatives, community members, guardians, and learners:

Thank-you so much for coming today and being a part of the launch of the very first One Laptop Per Child program in Gauteng.

My name is Olesia and next to me are my group members, Anastasia and John. We are Americans from Boston and we represent One Laptop Per Child, or OLPC, the non-profit that hopes to equip every child in the world with one of these durable, child-friendly green and white laptops.

And that’s why we are here today—because OLPC is donating a laptop to every grade 5 learner at the Lilydale Higher Primary School in Dlamini. Not only will these laptops be available for leisurely use at the school, but they will also be integrated into the classroom by teachers, and even the grade 6 and 7 learners will have the opportunity to learn on the laptop, which known as an XO.

You may have seen, heard or read about this laptop. It was specifically designed to be an affordable technological tool for a child under the age of 12 and has more than 10 educational programs already installed on it. It also comes with problem-solving games, a chat, and a network that allows up to 150 learners to work simultaneously on one project.

We are also very proud to announce that we are installing wireless internet at the school and providing a server to store hundreds of gigabytes of information, including digital textbooks.

During the winter break, when the learners were relaxing, these teachers—come on up!—were back at school—training how to use the laptops. I can confidently say we are very happy to have their full support and enthusiasm for this once-in-a-lifetime initiative.

Starting today, we will begin training the learners for an hour after school each day and as soon as next Monday, the teachers will begin using the XO during class time. The XO’s will move with the grade 5 learner throughout their time at Lilydale and will then be recycled and used by the incoming grade 5 class.

Although this is the first school project in Gauteng, 250 XO laptops were privately donated from two Boston sisters to the Kliptown Youth Program in Kliptown, Soweto. The Director of the Program, Thulani Madondo, is here representing the project, which is very familiar with the XO’s and has had a very successful tutoring program with them. Mr. Madondo has offered for several older KYP members to assist Lilydale teachers and learners with the XO after my team and I leave the country in August.

A letter has gone out to all the learners’ guardians about this program and we are looking forward to their feedback on an August 1st meeting.

I hope everyone is excited as my team and I about this project because you are all part of an exclusive number of schools receiving these XO’s all over the African continent. Over 30 teams from all over the world are across Africa right now doing the same thing we are in an effort to increase computer literacy. Teams in Ghana, in Sierra Leone, in Sao Tome, Ethiopia, Senegal, Congo, Nigeria—you name it. There are even two more South African teams in Limpopo province and the Cape, doing the same thing.

The goal is to show the power of this laptop so, with government involvement, the NGO can attain its mission: One Laptop Per Child.

Lastly, I’d like to express our enormous gratitude to Mr. Mohamed and all the teachers at Lilydale for being so receptive to this amazing program.

Again, thank-you so much for coming. Without further ado, lets donate these XO’s!

Last of Launch

Visual Display of the Last Few Weeks

Living in Luxury, South African Superstitions, Madiba Day, The Apartheid Museum, Violent Uprisings, Teacher Training II, and the OLPC Lilydale Launch

Sunday, July 26th

It has been one week since my last blog post and two weeks since I lived among a portion of South Africa’s forgotten citizens: the more than 10 million people—most of them unemployed—who live inhumane existences in neglected settlements surrounding major cities.

Life has changed drastically for me since leaving Kliptown. I am now living comfortably in a 24,000 square foot property on the cusp of Soweto known as Meredale. Across the road, Southgate Mall—complete with water fountains, escalators, movie theatres, grocery stores, and elite black South Africans whose tastes in apparel are just as haute couture as their taste in cars—constantly reminds me of neo-conservative, developed, privileged and consumerist South Africa—and it’s sharp disconnect with a vast majority of it’s inhabitants.

It pains me now to say that when I used to go to this mall while living in Kliptown, I felt at ease; no longer forced to stare poverty in the eye each time I dodged toxic puddles that separated densely-populated tin shacks adorned with young women washing, cooking, and carrying infants on their backs; no longer immersed in darkness early in the night; no longer looked at as a bitter enemy and beneficiary because of the color of my skin, I felt less responsible, more ignorant in the mall.

Mere steps away from indignity, rape, alcoholism, human toil, suffering, and the want for basic necessity, I wrapped myself in a purchase of an England soccer zip-up and a movie ticket at Southgate. Even in the depths of Soweto, I could not evade Hollywood and the fickle, hollow perception of security that mindless consumerism with it brings. Or maybe it was just the mall itself: a warm, safe structure conducive to the gathering and interacting of people. Even today, while I can’t be sure what made me feel so peaceful at that mall, I know returning to a routine of abuse, labor, and stunted growth in Kliptown was daunting.

But absence makes the heart grow fonder, and since my time away, I realize what a blessing being exposed to such a jolting reality was; indeed, often times I wish of trading in the heated carpet under my back, the omnipresent light between the shadows, the constant internet connection, and the padlocked gate around this castle which I now call home, for the endless internal thought and societal pondering that I could not escape among the petrol-smelling, dilapidated shacks in Kliptown.

The Afternoon of Monday, July 27th

Living in Luxury

Driving to Peggy’s that whirlwind Sunday afternoon, I knew my South African and Soweto experience would dramatically change, both for the better and worse. The wheels of Thulani’s car rolling through the winding roads of Meredale, an upper middle class, predominantly black suburb on the outskirts of Soweto, we finally arrived at our destination, not even the brick fence fortified enough to shield us from the sprawling garden—only half of which was budding because of the current winter season—that beautifully crawled up and down the big, brick house like an overbearing poison ivy. Two small cars stood in the gated garage behind the powered fence and across from the house as if to symbolize the only remaining piece of the rich man’s puzzle.

Thulani’s eyes widened as he personally came to grips with his country’s crude, abrasive economic disparities. After only having driven less than ten minutes, Thulani, who has admitted to wanting a better life outside of the slum because of his lack of retaining it—due to communal gossip, envy, and misconceptions—in Kliptown, was confronted with another world, a world that blacks have attained and live while his day-to-day is confined within a shack.

The gate opened while a small, aged, friendly white South African couple greeted us at the front door. We would soon be told that this was Peggy and Bruce, or Foss—full of shit, as Bruce likes to say—and Brucie, or Presh—short for precious, as Peggy adoringly calls him. As they gave us a tour of their house and the flat that we would be occupying for the next month, I watched Thulani become increasingly anxious and uncomfortable, his face either expressionless or full of anger and embarrassment, the former a reaction to centuries of discrimination and tyranny by whites, the latter an undeniable shame in, regardless of what anyone else thought, knowing what filth you came from and were shortly returning to.

Peggy’s sweet, white South African accent interrupted my powerless sympathy for Thulani.

“And although there is no washer and dryer in here,” she said as my gaze went from her mascara’d blue eyes, across the flat, through both sets of windows, and finally to the crisp, still baby blue waters of the swimming pool in their backyard, “we do have a washer in the spare room attached to the house.”

“Oh, so there is a washer,” I said, neither surprised nor disappointed.

“Of course,” she said, her mouth curdling to reach another puff of her cigarette, a permanent fixture in her hand. “I don’t do my own washing.” Although it was obvious Peggy didn’t have any ill-intentions or malevolent superiority in saying that, her innocuous comment was a perfectly smelted dagger in the heart of Kliptown, its words a constant reminder of the painful and seemingly permanent barrier between the haves and the have-nots.

After explaining that no, the flat wasn’t heated, Peggy stood over three invisible pads underneath the warm, fuzzy carpet, and said that once plugged in, the pads provided heat for the flat. Although I’ve never mentioned this to Foss or Presh, ever since tossing and turning in the cold on a rock-hard duvet that first Sunday night, I permanently relocated myself onto that heated floor, my preferred place of slumber until today.

Living in the flat reminded me what it was like to live in comfort, in luxury, in excess. It’s nice; neither necessary or unnecessary, heated floors, poorly-pressured shower heads, and hot water are undeniable satisfactions that more than half of the human beings living on this planet will not only ever enjoy, but will never even know the sensation of.

Alternatively, the flat has also brought uninvited problems into my daily routine. A long, confusing, impractical, and precarious walk from Kliptown, living here has banished me to a schedule not of my choosing. Instead of going to KYP to visit with Thulani, Pam, Christina, Nelly, and 375 of my closest brothers and sisters whenever I pleased or going for a run at the Kliptown field, my days are now filled with going to a fully air-conditioned, equipped, and modern gym, reading, and trying to get away from the relentless, persuasive beckoning of the single-most symbolic instrument of modernization, want, and mindless escape: the TV. Despite my earlier whining that living in Kliptown induced mental decay, it is surprising how little is accomplished in a modern flat where one’s personal space is limited, interrupted, and exploited by modern entertainment and interpersonal relationships.

South African Superstitions

After retiring around 10 PM the first night at Meredale, I fell fast asleep and woke early the next morning to find Bruce, who has accumulated his wealth by sustaining a lucrative blind manufacturing business, calling for Wonke, Bruce’s personal Zulu laborer who lives in a flat slightly similar—though less prestigious—to ours on Bruce’s property.

“Wooooonke,” Bruce loudly yells to the polite, 35-year-old Wonke, a man Peggy says is fine and good but is often spoiled by Bruce, who, according to Peggy, loans Wonke thousands of rand (ZAR), takes unexplainable days off without compensation, and cuts work. Wonke, who has three children to support, lives alone in the flat.

Yawning loudly and wiping my eyes with my fists, I walk towards the door facing the pool and turn the handle. Brucie, an avid conversationalist who will talk until either the sunset or narcolepsy hits his latest contender, spots me right away.

“Good morning,” he says, his bright blue eyes piercing mine, his Santa Claus stomach protruding from his torso slightly more than it was last night. “You haven’t seen the garden yet, have you?”

“No,” I said, perfectly conscious of just having committed myself to the arduous task. And so after an hour and half, I had finally seen the luscious Garden of Eden.

Mesh wire cylinders filled with rocks holding a pot of overflowing flowers, apples barely hanging on nails waiting for hungry birds, a myriad of different colored cacti, and water peacefully dripping from stone fountains, Brucie said the upkeep garden, which was, he carefully pointed out at least three times, both engineered and built with his bare hands, would not be possible without the help of hired weekly gardeners. He didn’t mention whether they were black or white.

South African Superstitions

Starring and diligently ‘ooo-ing’ and ‘aaahhh-ing’ at his various masterpieces and sometimes barely audible stories while my breath and urinary tract painfully reminded me of what I had left to do that morning, I noticed a break in Brucie’s stream of consciousness and decided to make a break for it.

“You see this,” he said, as if eager to foil my mental plan with a game of wits, “this I also made myself. He pointed to a bronze cutout figure hanging on the wall.

“Can you tell what it is,” he asked, hoping I wouldn’t guess.

“No, what is it?” I conceded.

“They are owls: scare away the blacks,” he said in a calculating tone, as if sharing an age-old secret with me. “They are afraid of owls, and snakes, too.” He pointed to his current work-in-progress, a slithering bronze snake. “If they see this, they’ll stay far away and never break-in. According to their tradition, or something. Weird, if you ask me.”

“Yeah, weird,” I said, glad I had stayed for the duration of the botanical tour to experience white South African stigma towards blacks, accurate or not.

Peggy and Bruce are not racists, nor do they hold certain stereotypes against blacks. Peggy is keen to recite me her favorite claim to fame on many an occasion: her brother Patrick was part of the South African Communist party and dedicated much of his life to the liberation struggle under apartheid before the iron hand of the Nationalists severely stifled any political dissent during the 1960’s with the passing of the sabotage, treason, and state of emergency acts that forced him into a self-imposed exile.

Peggy’s son has a black adopted son, and Brucie, although hesitant to admit Wonke as his ‘friend’ when I suggested as such, deeply cares for and nurtures Wonke as his own son, providing him a, relative to the standards of most black blue-collar workers, plush accommodation.

Despite those facts, Brucie has, more than once, admitted that for the majority of whites in South Africa during that blasphemous half a century—much like the majority of Russians and Ukrainians in the former Soviet Union who knew nothing of the outside world and swallowed Stalin’s propaganda of industrialization and growth through torturous five-year-plans and the supposed gains that came from the injustices of a communist despot—the prevalent idea of the white minority as inherently superior over the black majority held a lot of weight—the untangling of such an engrained theory would take Bruce almost 60 years to accomplish, he admits.

Still, despite their egalitarian stance—both in speech and practice—towards the 80% of the citizens in South Africa, there are times when imperialist philosophy can’t help but seep into kitchen conversation.

“But when you think of it,” Brucie says, not wholly confident, perhaps still reciting his high school lecture, “most of the countries in Africa would not be where they are today without the white colonizers. They built infrastructure, developed industry, and invested in trade.”

Although an argument I have heard before, even from the most liberal Iranian professor at UMass Boston when making a case for colonization, I decided instead of picking a useless fight, to give myself the most valuable of gifts: attentive listening.

But Peggy changes the subject.

“You know one thing that continues to make me mad about Patrick is the stuff that comes out of his mouth sometimes,” she said after a long and what appeared to be pleasing drag of her cigarette. “You know my son’s adopted child, the black one,” she said as she waited for my confirmation of her statement.

“Yes, I remember,” I answered.

“Well I remember a few years ago Patrick telling Dwayne, my son and the adopted father of this black child, that it wasn’t right adopting him and that the child belongs in his own culture, with other blacks. Can you believe that? And he even tells us that we don’t belong here in South Africa—that we should move.”

“And what does he suppose he’s doing here, living in the Cape, being just as white as you are,” I asked, dumbfounded that a liberal freedom activist who supported Mandela—a brave man who helped pioneer the non-partisan and multi-racial Freedom Charter, a document promulgating a united country for all South Africans—would disprove of a mixed family.

“I know,” Peggy said, “he’s insulting.”

Far from the racial harmony and understanding that the most ethnically and racially diverse country on the continent strived for at the onset of democracy in 1994, South Africa is still at bitter war with itself: whites, regardless of whether they are Afrikaans or not, continuously find themselves defending their political and cultural beliefs in the face of criticism again racism, historical affiliation, and work ethic, as a result finding solace only in other whites who bear the same societal burden—as the obvious minority—ultimately acting to strengthen ties between their cohesive community; Indians and coloreds are also united in their defense against the blacks, who resent their historical privileges during apartheid and continued affluence; while blacks—or Bantus, the name of South Africa’s original inhabitants who traveled from the Niger-Congo region—who comprise 80% of the country, psychologically revolt against all other creeds and colors, including blacks of other tribes (such as a recurring theme on the most popular Soap Opera in the country, Generations, where a ‘gogo’, the local term for grandmother, persistently, and in no nice terms, tries to persuade her Zulu granddaughter to give up her dreams of marrying ‘that Xhosa boy’) in an effort to show their disdain towards the stark socio-economic differences that persist in the country today.

And still there will always exist the rare anomalies that confuse South Africa’s mixed political and ethnic landscape even further: elite blacks who, after working on gold mines, being employed by Afrikaan masters during indentured slavery, or going to a prestigious school, speak Afrikaans and are ostracized by the rest of their race; radicals like Patrick who think racial integration constitutes yet another form for white imperialism; or people like Peggy and Bruce, who, despite their most genuine efforts to remain just, constantly fight capitulating to stereotypes against blacks when they get stopped at a red light in Johannesburg by a threatening black man who demands money, as was the scene last week, a perturbed Peggy explained.

An extremely difficult country in which to live because of the visual contrast of us against them, or ‘the other’, and the multi-dimensional hierarchy of wealth and power, South Africa today is more divided than it is united. Indeed, many blacks have been left out of ‘Mandela’s South Africa.’

Madiba Day

Madiba, Mandela writes in his ‘Long Walk to Freedom,’ is both the anti-apartheid hero’s Xhosa clan name and the name of one of his many sons, all spawned by different wives.

Madiba is also the endearing term which garners the most respect for the now ailing former President, and when Nastya and I were watching TV last Saturday, Nelson Mandela’s 91st birthday, that term was most often used when referring to the ‘inspiration’ and ‘pride’ the living national icon instilled in not only South Africans or Africans, but the human race.

Throughout the duration of the day, TV programs had entire segments dedicated to Mandela the child, Mandela the Xhosa, Mandela the teenager, the man, the political pioneer, the prisoner, the president, and the legend. Men who spent many of their lives in Robbin Island with Mandela, former ministers in his administration, friends, and colleagues all donned themselves to speak about their experiences with Mandela; helicopters equipped with long-range video cameras swarmed Mandela’s mansion in Haughton—a multi-millionaire enclave of exquisite wealth, rivaling some of the most expensive and elegant Hollywood homes; and people all over the country were beckoned to do a selfless deed in their community for 67 minutes, a figure which, when subtracted from the current year, represents the year Mandela officially acted on his political consciousness and embarked on his long walk to freedom, beginning with rejecting the conventional wisdom elite blacks were taught about the honorable Englishman and climaxing with Mandela’s attendance at his first ANC meeting.

The only man missing from the elaborate celebration was Nelson Mandela, whose old age and deteriorating mental and physical health have been cited as reasons for the charismatic leader’s increasingly common absences at public events.

The Apartheid Museum

Keen on avoiding what was sure to be long, winding lines of locals and tourists alike at South Africa’s most comprehensive Apartheid Museum, my group and I decided to pay tribute Sunday to the most sophisticated and long-lived example of institutionalized racial segregation in the history of mankind.

The museum itself is situated right off the M1 highway, between Johannesburg and Soweto, on the same plot of land as Gold Reef City, a property now an amusement park but long ago one of the vastest gold mines, one that was owned by whites yet labored by black South Africans and foreigners from across the continent looking for work during an industrial boom. Workers were paid next to nothing in return for working more than 12 hours, were mistreated, beaten, exploited, and if lucky enough to survive the wrath of their master, died in work-related accidents in record numbers; the rich history of South African protest and revolt began with one of the largest mineworkers strikes organized by the Communist party and the ANC in 1946.

At the entrance of the museum hung three identical banners, approximately 20 feet high and 4 feet wide, that bore Mandela’s face in different colors—not unlike Andy Warhol’s iconic Campbell’s soup cans. The museum, a large building that inside traveled through time with each tourist like a labyrinth, was more wide than it was tall, made purely of brick, and completely unassuming. In an effort to evoke emotion and create a sense of identification between the subject and the historical implications of apartheid, museum staff recreated the entrance as a typical 1950’s or 60’s South African entrance.

“European Entrance Only, by Order” the sign above John’s head read. The museum employee motioned him and Nastya through it.

“Non-European Entrance Only, by Order” was the sign under which I was told to walk. And so I did. Checking my dignity, pride, morals and smarts, I was now just a thing, distinguished only by race and the inability with it associated. I walked underneath the sign, between the walls, through the entrance and into a room full of giant ID cards that classified people as either Zulu, Xhosa, African, European, Colored, or Asian; as with all other layers of apartheid, material goods, including ID cards, become more desirable with rank—unchanging, permanent, hereditary rank. While the cards—referred to as passes, to be shown by all citizens at all times to enforce apartheid rules and regulations such as residency, familial ties, and segregated employment—for Europeans were professional and organized, the cards for Zulus were thinner, carelessly signed, an lacking order. Although by 1955, eight years after apartheid, some 12 million people had been registered under the Pass System, the security measure was in reality implemented to control and targeted at South Africa’s silenced democratic voice: blacks.

The museum, complete with riveting photography, video, audio, hanging nooses, regulation prison cells, Nationalist propaganda in the form of newspapers, radio broadcasts and movies reminiscent of Hitler’s Mien Kampf, and millions upon millions of words of commentary, was a vast time capsule that left no injustice unprovoked.

After the Brits and Afrikaans signed their Treaty of Union peace accord 6 years after the end of the Anglo-Boer War, they drafted a constitution that largely left out South Africa’s primary inhabitants, blacks. This marked the motivation for the 1912 inception of the ANC. After contestation within the organization about whether or not to support struggles at the same time independent and overlapping with ANC principles of democracy and racial unity, the ANC unanimously agreed upon a coalition of forces including trade and labor unions, communists, feminists, Indians, and Coloreds, forming a hypothetical document called the Freedom Charter, signed in Kliptown in 1955. The beginning of defiance against the state also marked the escalation of its suppression: the violent quelling of women’s revolts against the government banning their homemade beer production, one of the only sources of income for African women, made international headlines, as did the enormously successful 1952 Defiance Campaign.

Mandela, who was one of the architects of the ANC Youth League—a younger, more exuberant ANC branch meant both to bolster membership and revitalize the dimming organization—was also an ardent proponent of racial inclusion in the ANC and the most faithful advocate—in the face of strong opposition—of the MK, the ANC’s military wing.

Once Mandela was certain that freedom could be achieved only by taking up arms and fighting the state with its own weapon of callous indifference, the MK began training for acts of sabotage, guerilla warfare, and ultimately, revolution. Mandela was sent to Ethiopia to meet the last emperor, to the Congo, Sudan, and at least five other countries on the continent to secure regional support and funding for what would become South Africa’s ‘final solution’ to apartheid; he was arrested in Durban upon his return and sentenced to five years in prison. Once the MK headquarters was raided two years later, Mandela and half a dozen other MK organizers were spared the death sentence and charged with life imprisonment on Robbin Island, a time during which the strength of the ANC waned and labor unions such as COSATU played an integral role in mobilizing radical opposition to apartheid policies.

The last two decades of apartheid were marked with the most radical, mobilized, and determined youth movements in South African history, leading to the famed, bloody 1976 Soweto uprisings, a single picture of which remains one of the most memorable of all time: A crying woman, with fear and irreversible devastation in her eyes, as the backdrop to a young, bleeding, unconscious man being frantically carried away during the riots that left hundreds dead, most at the hands of vile and careless police brutality. The young man, who died instantly, was Hector Petersen, to whom a Museum is dedicated in Soweto; his sister is one of the KYP board members and I plan to interview her at the next meeting in early August.

The Nationalist reaction to the stiffest form of defiance the state had ever seen was unprecedented: torture—including rudimentary water boarding—exile, lifetime imprisonment, draconian prison sentences, summary executions, political assassinations, and assisted suicide were all tools by which to punish, muffle, and prevent opposition. The sporadic yet nevertheless practical use of biological and chemical warfare by the Nationalist government against political dissidents, later to be sold and used in Angola, was another covert instrument of the state.

Although the scars of apartheid were deep and the casualties many, the loss of life during the transition period to democracy, from 1991-1994, were more than four times that of the apartheid era. With Afrikaan communities betrayed over the Nationalist government’s concession to hold peace talks with kaffirs, the Afrikaan term for the N word, black communities betrayed over the ANC’s concession to hold peace talk with the devil, and bitter in fighting among ethnic South African blacks, the country that was praised for being the only in the history of mankind to come to democracy without a battle was indeed on the crumbling verge of civil war.

After Mandela’s release from Robbin Island following 27 years of imprisonment, a portion of which was solitary, the man with the support of the nation was able to quiet the people.

Peggy’s chilling words still echo in my head: “If that man, and I can’t even say his name because I’ll cry, if that man came out of prison and he was mad….”

She didn’t have to finish. I did for her.

“He could have incited a civil war,” I said. The room fell silent with concurrence.

Violent Uprisings

8 Minutes to Midnight, Monday, July 27th

“Many blacks have been left out of Mandela’s South Africa…..”

Referred to as ‘service delivery’ protests, slum riots have captured the front-page news again and again the last few weeks: one in Durban, one on the outskirts of Johannesburg—all desperate, all violent, all hopeless.

Midnight, Tuesday, July 28th

Images of burning tires surrounded by angry faces waving metal rods and clenched fists fill South African newspapers daily as of late. Underneath the photos, journalists quote locals proclaiming to be ‘tired of broken promises’ by ANC councilors and ‘demand to have their needs met.’ Those unmet needs—lack of electricity, power, infrastructure, health care, and education—are the same as the needs of millions of others waiting to die in South African ghettoes, all of which were, according to the ANC, slated for abolition in 1994.

‘SERVICE DELIVERY RIOTS TURN XENOPHOBIC,’ one headline read last week about the Durban riots, which began with loud singing and chanting and evolved to the violent looting of shops owned by Ethiopians and Zimbabweans.

12 months shy of the Soccer World Cup, suffering South Africans continue to have at their whim plenty of attention—and courage—to exploit towards their own justified ends.

At last word, the Zuma administration appointed a committee to investigate the so-called lack of ‘service delivery’.

Teacher Training II

Early Tuesday Morning

The second batch of teacher training—consisting of the ten out of the total 13 teachers at Lilydale—occurred on the 15 and 16th of July, when we met with the teachers for four hours each day. Although we had two previous teacher training sessions in late June where all teacher attended, disparities between the rate of understanding were evident among the teachers and it was obvious we had to start from scratch—not a play on words, for all those OLPC-friendly readers who may be confusing ‘scratch’, the term used to refer starting from nothing, to ‘Scratch’, a program on the XO that allows the user to create graphic animations and designs—during both July sessions.

The days were divided by a noon lunch; the first portion of the day revolved around basics such as battery life, turning your XO on and off, saving files, a brief introduction into the most useful—subjective indeed—programs on the XO such as Read, Write, Calculate, Scratch, Record, Memorize, and Wikipedia, navigating your XO, accessing the mesh network, and most importantly, stopping functions using the border.

Although most of the teachers’ English skills were commendable, to some teachers, who have never even used a computer before, if was tough to teach simple technical lingo that we take for granted, such as mouse, hover, drag, ect. Phindile, who acts as the spokesperson for all the teachers at Lilydale, instructs math, and speaks almost impeccable English, had the XO down in a matter of hours and her agitation for the redundancy of the training was apparent. That redundancy was also necessary, though, for teachers of the Zulu tongue, like Job, had a very difficult time keeping up with the speed of the training and almost at all times required assistance.

Because we didn’t want to have the teachers constantly depend on us for help and instead wanted to empower them with the tools necessary to lead a successful school deployment at Lilydale, we decided it best to prepare subject-specific questions that can be solved using programs on the XO—and require navigational skills to complete—for the teachers. In total, four questions based on Math, Science, English and Social Studies were created. The teachers did relatively well, completing—in varying degrees of success—the first two problems. The next day, the teachers worked on the remaining two problems for the first two hours and following lunch, we discussed practical matters including their thoughts on the deployment, on the XO, on its practicality in class, the storage of the XOs, and the most contentious issue to the teachers—while the most integral to the OLPC mission—the ownership of laptops.

Although all of the teachers at the first training agreed that the idea of joint ownership—official ownership of the XOs would be had by the school while each student would be granted the opportunity to take their marked XO home once the learner, as they call students in South Africa, demonstrated a commitment to the program and his/her education—could be successfully enforced at Lilydale, the second batch of teachers were opposed to it entirely, or at least until they could discuss the advantages and disadvantages in depth as a collective group.

Most of the teachers agreed with Phindile that the XOs, especially in a high-risk area like Soweto, represent an attractive bounty for criminals.

“We are worried that when these kids take the XO home, their unemployed brothers, sisters, and maybe even parents, will steal the XO and sell it, or keep it for themselves,” Phindile said during day two’s discussion to the agreeable murmur of the group. “So I don’t think we are prepared right now to make that decision, but we are so grateful to have been chosen as the school receiving these computers.”

Similar heartfelt sentiment followed from the rest of the teachers as we wrapped up the training session and began talking enthusiastically of the July 22nd launch.

“We truly feel so blessed to be a part of this project and we are so excited to begin,” said Joyce, a grade 5 Social Studies teacher.

“So you think you will be ready to incorporate the XO into your curriculum as soon as next Friday,” I asked with hesitation.